Future Drainage 2025 | Roundtable Reflections

Local authorities are increasingly aware that future drainage and flood risk cannot be managed through response alone. The third roundtable focused on preparedness: how ready organisations feel to deal with major events, how far their approaches have evolved, and what still stands in the way of longer-term planning.

Across the discussion, delegates described a sector that has learned a great deal from recent flooding, but remains constrained by short-term funding models, limited resources and uneven access to data. Preparedness is improving, but largely in a reactive sense. Proactive capability remains harder to embed.

How Prepared Do Authorities Feel Today?

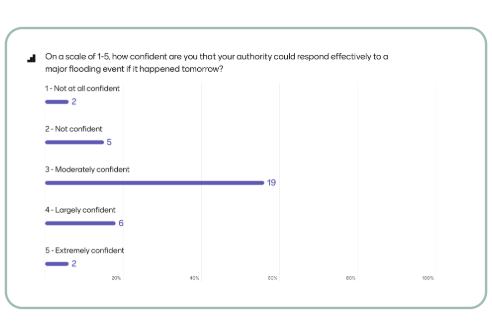

The session opened by asking how confident authorities would feel responding to a major flooding event if it happened tomorrow. Most delegates placed themselves in the middle of the scale, describing a position of moderate confidence rather than certainty. Only a small number felt extremely confident, while a meaningful minority still reported low confidence.

This reflected what many described as “hard-won readiness”. Experience of past events has strengthened response arrangements, but that confidence is often tied to people, not systems. Several tables referred to a persistent “firefighting” mode: teams know how to respond, but preparation is still shaped by available funding, staffing and the immediacy of risk, rather than long-term resilience planning.

Figure 1: Confidence in responding effectively to a major flooding event.

Figure 1: Confidence in responding effectively to a major flooding event.

Change Is Happening, But Incrementally

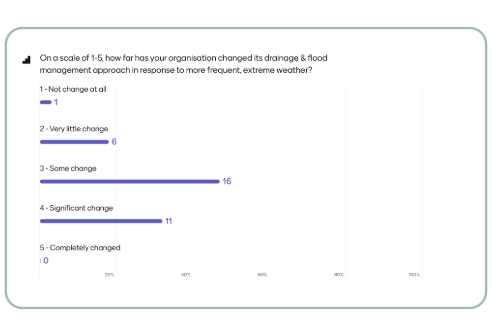

Delegates were then asked how far their organisations have changed their drainage and flood risk approach in response to more frequent extreme weather. Most reported some or significant change, suggesting that lessons are being absorbed. However, no authority felt their approach had been completely transformed.

This reinforced a consistent message: the sector is evolving, but not at the pace or scale many would like. Change is often incremental, driven by individual events, inspections or funding windows, rather than by a sustained strategic shift. Experienced authorities, particularly those that have dealt with repeated flooding, were often further ahead. Others acknowledged that change still tends to follow incidents rather than anticipate them, reinforcing the sense that learning remains largely reactive rather than embedded through long-term planning.

Figure 2: Extent of change in drainage and flood risk management approaches.

Figure 2: Extent of change in drainage and flood risk management approaches.

What Authorities Want to Do With Better Data

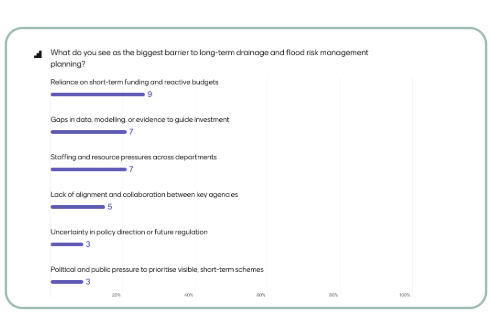

The clearest headline from the roundtable emerged when delegates were asked about the biggest barrier to long-term drainage and flood risk planning. The most common response was reliance on short-term funding and reactive budgets.

Delegates described funding cycles that prioritise visible, immediate action over sustained investment in preparedness. This makes it difficult to commit to surveys, modelling, skills development and preventative work, even where the need is well understood.

Closely linked to this were gaps in data, modelling and evidence to guide investment. Many authorities acknowledged that while they know what needs to change, they often lack the confidence or evidence base required to justify longer-term decisions within existing funding frameworks.

Figure 3: Biggest barriers to long-term drainage and flood risk planning.

Figure 3: Biggest barriers to long-term drainage and flood risk planning.

The Role of Data and Technology in Resilience

Data and technology were widely seen as part of the solution, but not a silver bullet. Delegates discussed growing interest in rainfall forecasting confidence, sensors, risk matrices and combining survey or CCTV data to better understand network capacity and performance.

Several tables highlighted the importance of integrating datasets across teams and agencies, rather than collecting more information in isolation. Where data remains fragmented, confidence suffers and opportunities for proactive planning are missed. Some authorities also described “living” flood plans, updated as conditions, assets and risks change, rather than static documents revisited infrequently.

Public Engagement and Shared Responsibility

Another strong theme was the role of the public in future preparedness. Delegates repeatedly highlighted the strain caused by misunderstanding of drainage systems, flood risk and responsibility.

Examples of more proactive engagement included “adopt a gully” schemes, leaf wardens, driveway reporting and clearer online guidance. These approaches were seen as practical ways to reduce avoidable callouts, build shared understanding and support communities to play a role in resilience.

Several tables noted that while awareness is improving, belief and acceptance lag behind. Moving towards a culture of “living with risk” requires consistent messaging and political support, particularly where flooding cannot realistically be prevented everywhere.

How the Sector Moves Forward

Despite the challenges, the discussion pointed to several areas where progress is already happening or clearly needed:

• Shifting funding conversations

Building evidence that supports longer-term investment, rather than short-term response.

• Strengthening data confidence

Improving access to modelling, surveys and performance insight to guide decisions and justify change.

• Embedding resilience thinking

Moving from defence to adaptation, recognising that flooding cannot always be avoided.

• Investing in people and skills

Retaining experience and supporting training to reduce reliance on individual knowledge.

• Engaging communities more effectively

Clearer communication and practical schemes that support shared responsibility.

These steps reflect a sector that understands what needs to change, even if delivery remains uneven.

Conclusion

Roundtable 3 highlighted a sector becoming more realistic about future flood risk. Preparedness is improving, particularly in response capability, but longer-term planning is still constrained by short-term funding models, resource pressures and gaps in evidence.

The clearest message from the discussion was that future resilience will depend less on reacting better, and more on planning differently. That means investing in data, skills and engagement that allow authorities to move beyond firefighting and towards sustained preparedness in a changing climate.